Some years ago, I struck up a conversation with a young writer at a convention. (I love getting to know other writers, so this is not unusual for me.) One thing led to another, led to lunch, led to getting together on a regular basis, and led to frequently chatting online. I cheered her on as she had her first professional sale and then another, and then a cover story in a prestigious magazine. One of the gifts of such a relationship is not the support I receive from it, but the honor and joy of watching someone else come into her own as an artist, to celebrate her achievements. It's the opposite of Schadenfreude -- it's taking immense pleasure and pride in the success of someone you have come to care about.

Monday, July 31, 2023

Writerly Support Goes Both Ways

Some years ago, I struck up a conversation with a young writer at a convention. (I love getting to know other writers, so this is not unusual for me.) One thing led to another, led to lunch, led to getting together on a regular basis, and led to frequently chatting online. I cheered her on as she had her first professional sale and then another, and then a cover story in a prestigious magazine. One of the gifts of such a relationship is not the support I receive from it, but the honor and joy of watching someone else come into her own as an artist, to celebrate her achievements. It's the opposite of Schadenfreude -- it's taking immense pleasure and pride in the success of someone you have come to care about.

Friday, July 28, 2023

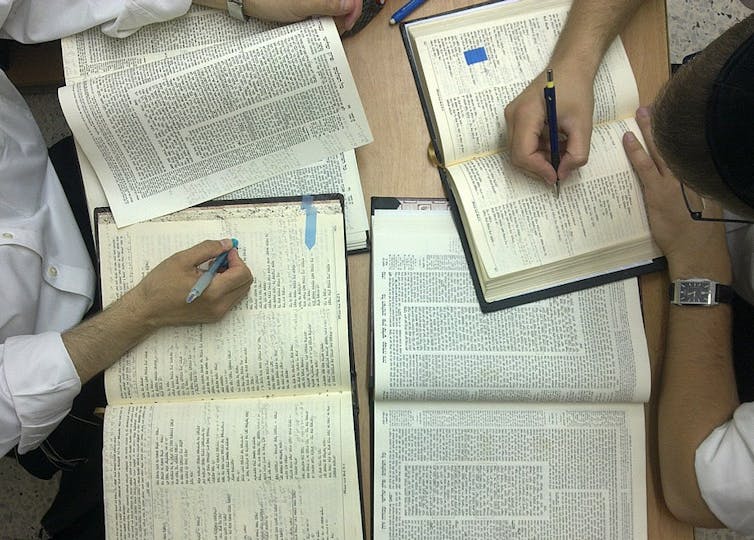

Reprint: Nonbinary gender in Jewish law

Nonbinary genders beyond ‘male’ and ‘female’ would have been no surprise to ancient rabbis, who acknowledged tumtums, androgynos and aylonot

“Genderqueer” and “nonbinary” are contemporary terms for people who don’t fit neatly into male or female categories. But acknowledging that not everyone fits neatly into those two groups has a much longer history than you might suspect.

As a scholar of Judaism and gender, I find that people across the political spectrum often assume religion must be inherently conservative and unchanging when it comes to sex and gender. They imagine that religions have always embraced a world in which there are only men and women.

But for Judaism – and for many other religious traditions, too – history shows that’s just not true.

More than two terms

Traditional Jewish sources discuss the categories “man” and “woman,” but these aren’t the only designations rabbinic texts use for sex and gender.

Rabbinic literature, the body of texts written by Jewish leaders in antiquity, includes several other categories. In these texts, a person with both sets of external genitalia is called an “androgynos,” a term borrowed from Greek. A person with neither is called a “tumtum,” and a person who loses his male sexual organs is called a “saris.” There is also a term for someone whose sex assigned at birth is female but does not develop to female sexual maturity – in some cases, because they develop “male” traits: an “aylonit.”

For example, Genesis Rabbah, a collection of creative Biblical interpretation from late antiquity, records an interpretation of a creation story in the biblical book of Genesis in which God forms the first humans. Genesis 1 includes the phrase, “Male and female He created them,” which many readers interpret to mean that God created a man and a woman.

But some of the rabbis quoted in Genesis Rabbah believed that God had made an androgynos.

One rabbi explained: “In the hour when the Holy One Blessed Be He created the first human, He created an androgynos, as it is written, ‘male and female He created them.’”

Genesis Rabbah continues with another rabbi’s argument that God made the first human with two fronts: a female face and body facing one way, and a male face and body facing the opposite direction. Only later did God split the two, in this rabbi’s reading.

Though the specifics of their interpretations differ, both put an androgynos at the center of God’s creation.

Applying the law

Jewish law, or halakhah, is based on a gender binary. For example, some commandments, such as studying Torah or not shaving sidelocks, apply only to men; others, such as Sabbath candle lighting, apply only to women.

However, some halakhic traditions also recognize that not every person’s body fits that binary.

The Mishnah, a text compiled in the third century C.E. which includes halakhic material, roots its interpretations in the categories men and women, yet also affirms the idea that sex and gender go beyond those terms.

For example, a section called Mishnah Bikkurim explains: “There are some ways the androgynos is like men, and some ways he is like women, and some ways he is like men and women, and some ways he is like neither men nor women.” Another section of the Mishnah explains that, like women, neither a tumtum nor an androgynos is obligated to go to the Temple in Jerusalem as part of certain religious festivals. Meanwhile, an androgynos must dress like a man, and a priest cannot marry an aylonit unless he already has children.

As these examples suggest, gender diversity is woven throughout rabbinic traditions. Yet there is still a hierarchy, with men holding positions of the highest religious obligation.

It is also important to note how these categories differ from the ways people understand gender today. A nonbinary person in the 21st century does not have the same experience as a tumtum in late antiquity. The idea of “aylonit” does not map clearly onto any common gender identity today. Even the term “androgynos” is not quite the same as intersex. And none of the rabbinic categories match current ideas about trans identity.

Forging a future

In spite of this textual tradition, many observant Jewish communities today still tend toward a gender binary. In most Orthodox synagogues, for example, a physical partition divides the worship space into two sections: one for men and one for women. Halakhic rulings about whether and how parents should support medical interventions on intersex children suggest they should be raised as male or female, not as an androgynos or tumtum.

In other Jewish communal spaces, however, traditional texts have become a resource for contemporary LGBTQ+ Jews. Some look to these texts to affirm their beliefs that Judaism has always seen gender diversity as a spectrum. Others use these texts to see themselves within Jewish tradition. Still others use these examples to call for change in the present, countering anti-LGBTQ+ positions.

Many of these Jews recognize that the diversity of sex and gender in these ancient texts is different from gender identity today, but they believe the past can still serve as an important tool in the present.

Rabbinic texts illustrate that there is no magical time in the past when every person fit easily and naturally into gender categories.![]()

Sarah Imhoff, Professor of Religious Studies, Indiana University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Monday, July 24, 2023

Midwifing a Story: Beta Readers and Critiquers

Friday, July 21, 2023

Short Book Reviews: A Time-Twisting Space Mystery

Eversion, by Alastair Reynolds (Orbit)

Alastair Reynolds is one of my favorite writers of hard

science fiction. His stories sweep me up in adventure, mystery, and very cool

ideas. With Eversion, he’s reached new heights of complex yet rewarding

storytelling. In it, he builds mystery upon mystery, with each layer adding

connections and insights. He always “plays fair,” giving the reader everything

they need to understand the characters and the dilemmas he has thrust them into

at that moment. The book is a primer of brilliantly handled plot twists!

The story begins as a sea adventure: an 1800s expedition to

discover an enigmatic structure, “the Edifice,” deep within a fissure in the ice

cliffs of Norway. The narrator is the ship’s physician, recruited at the last

minute and therefore not on the ship’s manifest. As he performs his medical

duties, he develops relationships with the rest of the crew and passengers,

including the arrogant tycoon who’s financed the expedition, a brilliant but

tortured young mathematician, and a disturbingly flirtatious woman who seems to

have no other function than to torment the doctor. Soon, however, things go

horribly wrong. Even as the ship finds the bizarre, possibly inhuman structures

of the Edifice, it also discovers the wreckage of an earlier ship, one the tycoon

lied about… and then the doctor dies and finds himself a century later on an

airship encountering the Edifice in a different, expanded form, and the

previous ship, but with strange, fragmented memories of having been in a

similar situation before. With each iteration of an exploration gone horribly

wrong, the doctor makes new connections and comes closer to what’s really going

on, the truth beneath the narratives. It’s a gorgeous spiral of self-discovery,

tense action, and ultimate sacrifice.

Monday, July 17, 2023

Write What You Love

Don’t try to figure out what you must write to get published or make the bestseller list; write something that excites you. If you look at most first novels, even ones that aren’t particularly good, they all have a certain energy that comes from a writer getting an idea that excites them.

I think this is right on target. If you look at what's hot now, you're looking into the past. A traditionally published book often takes about a year from its acceptance to its appearance in bookstores. Many times the lead time is longer. The manuscript must be edited and revised, copy-edited, and proofread. Cover art must be commissioned, sketches reviewed and approved, and cover designed. Sales teams need catalogs about six months in advance. That's not counting advance reading copies (ARCs) to review venues like Publisher's Weekly. Finally, the book must be printed and distributed so that it is available at your corner bookstore on or slightly before the release date.

Even with e-publishing, which does not require the long lead times for preparation and distribution of the physical book, there is a gap between the finished product (which hopefully has been through a similarly-rigorous process of editing and proofreading, not to mention cover art and design!) and the initial conception of the author -- the decision to write this particular book. Writers vary in how long it takes to write a novel. This involves not only the speed of creating that first draft but on how much revision the draft needs. And how committed we are to making each book the very best we can, which means both learning our craft and not turning out hastily-written slip-shod work. For most of us, care requires time.

So the ebook or print book you see in the stories may have taken anywhere from 6 months to 6 years in creation. Who wants to be that far behind the times? More to the point, who wants to spend that much of your writing career imitating what someone else was excited about 6 years ago?

Fads will come and go, tastes will change with the seasons. Publishers merge or fold and even more arise. Wonderful books receive lousy promotional support and fizzle. Mediocre ones catch the public's fancy and make pots of money. We as writers have zilch control over any of this. I truly believe that chasing the market is not only futile, but deadly to our creative lives.

The only way to have a satisfying career is to write what you love. It is not enough to guarantee commercial success, but without it, you might as well take a job as an accountant. The paycheck's a whole lot more reliable.

If you've enjoyed this essay on nourishing yourself as a writer, please check out my collection, Ink Dance: Essays on the Writing Life. It's filled with stories, advice, commiseration, and inspiration.

Friday, July 14, 2023

Short Book Reviews: Deadly Secrets: A Brilliant Depiction of a Trans Teen

Mad Honey, by Jodi Picoult; Jennifer Finney Boylan (Ballantine)

Jodi Picoult’s writing never fails to blow me away. She

tackles complex and difficult issues with compassion, nuance, and page-turning

drama. I’ll gladly gobble up anything she writes, so I nabbed a copy of Mad

Honey without reading the description. I wasn’t familiar with co-author Jennifer

Finney Boylan; Picoult’s name on the cover was enough to sell me. And what a

journey the two of them took me on! The collaboration was a brilliant idea, a

duet of two distinct voices with two authentic life experiences.

I won’t elaborate on the plot too much, because the plot

twists are half of what kept me up way too late, turning the pages. Suffice it

to say that the backstory of boy-meets-girl, each from a family with hidden trauma,

quickly explodes into tragedy. From there, the story—told in alternating points

of view of the girl and the boy’s mother—plays out from that turning point, one

story unfurling into the past, the events leading up to the crisis, the other

taking the story forward. If this sounds confusing, it isn’t. The dual timelines/narrators

layer connection upon connection like a four-dimensional tapestry. I found

myself falling in love with characters and wishing them happiness even when I already

knew this would never be their fate.

It is a mark of the skill of the authors and their chosen narrative

structure that the twin struggles of a trans teen coming into their own and an

abused woman seeking safety and empowerment perfectly mirror and inform each

other. The story left me wanting to rush up to everyone I know and demand that

they read it!

Monday, July 10, 2023

Student Artists Interpret "Four Paws To Light My Way"

My friend and colleague, teacher Tanja Nathanael, includes "Four Paws To Light My Way," my story about a blind swordswoman and her guide dog, in her classes. She asks the students to illustrate it, and has been kind enough to forward some of these amazing drawings to me. Here are some of my favorites.

Friday, July 7, 2023

Short #BookReviews: A New Tiger and Del Novel from Jennifer Roberson

Sword-Bearer, A Novel of Tiger and Del, by Jennifer Roberson (DAW)

Ah, the pleasure of sitting down with a new Jennifer

Roberson novel, especially a new Tiger and Del novel. From the first paragraph,

I know I am in the hands of a superb storyteller. I’ve been following the

adventures of “the Sandtiger” and Delilah since Sword-Dancer introduced

them to a world of adoring fans. It’s taken them a number of novels and many

adventures to come to a mutually respectful, often passionate relationship. In

the process, Tiger has discovered his own innate talent for magic, something he

never wanted and has done his best to rid himself of.

Now they’ve settled into a life of respectability, raising

their young daughter while teaching student sword-dancers and owning a share in

a local cantina. All that comes to a crashing halt with a series of bizarre,

terrifying weather catastrophes. They’re off on another adventure to discover

the source of the storms, a quest that will demand every bit of magic and sword

skill the two can muster.

The plot description doesn’t come close to capturing the

magic of the story itself, the memorable characters and their choices, the

harshly gorgeous landscapes, the sizzling action, superbly handled tension,

evocative details, and plot twists. I love the vividness, courage, and frailties

of Roberson’s characters. In her hands, the most extraordinary heroes become appealingly

human. Most of all, though, the books portray the abiding love between Del and Tiger,

their devotion based on trust and respect, with generous moments of juicy desire.

I love how they’re each able to accept differences of opinion without the

slightest doubt and to rely not only on their own skills but their partner’s. Eight

books later, the romance is still alive. Not only alive, but deep, quiet, and true.

If this, for nothing else, the Tiger and Del books are worth cherishing and

re-reading.