Gender, Capitalism, and Labor: The Relationship Between Economic Self-Reliance and Well-Being in American Women

by Sarah Madeleine Wheeler

The proposition that “Throughout U.S history a woman’s capacity for economic self-reliance is the most important determinant of her well-being” is not unreasonable and is well-supported by evidence; however, it is incomplete and fails to extend into the critique of capitalism, power and class disenfranchisement that is necessary for a well-rounded understanding. In any capitalist system, the powerful will seek to deprive the disadvantaged of monetary resources, the better to retain and stratify their own class privilege, and to maintain a desperate class of workers willing to labor on starvation wages. While the American race-caste system, dating back to the 1681 statues made in reaction to Bacon’s Rebellion (How America Invented Race, 2020), was orchestrated with the suppression and control of minority labor forces in mind, the domination of the largest minority on Earth pre-dates the invasion of the continent and composes the oldest form of unpaid labor. That a woman’s economic self-reliance is primary and critical to her well-being is true insofar as any disadvantaged person’s economic fortunes is thusly important to their fate within the capitalist system; that is to say, women’s rights are human rights and human rights are labor rights.

Prior to and during the strict control of women’s capital

via legal statute, women frequently were capital, a reflection of both their

reproductive capacity and of the unpaid labor they were expected to perform. From approximately 1600 onwards, both

colonialist and Indigenous women (and children) functioned as chattel and

“valuable cultural commodities to be taken hostage and exchanged” for inanimate

objects and other capital (Brooks, 1996).

In the wake of Bacon’s Rebellion, women were key to controlling the

labor force through racial categorization; miscegenation laws combined with “according

to the condition of the mother” clauses (Hening, 1823) ensured that neither

women of color nor their descendents would have access to either freedom or

capital of their own. As systems of

power and control began to emerge, those women whose labor was not controlled

by systems of servitude and racial disenfranchisement were constrained by the

laws of men which erased their separate legal identities after marriage and

stripped from them most claims to capital and property, a system known as coveture. The twin American disenfranchisements, on the

basis of sex and on the basis of race, had devastating consequences for women’s

well-being. For instance, renowned poet

Phillis Wheatley, the founder of multiple American literary traditions, died at

31 years of age in wretched poverty as she struggled alone to support an infant

son by working as a scullery maid, on account of both her race and her sex

(Wikipedia, 2021; Phillis Wheatley clip…, 2014). Even Rachel Wells, a White woman who lent the

hefty sum of £300 from her own resources to fund the Revolutionary War and

therefore should have been a valued patriot, could not get her bond returned on

account of her sex and was reduced to sleeping on straw in her old age, begging

piteously in misspelled letters to Congress for “a little [interest]” from her

‘borrowed’ funds (Living Through War & Revolution, 1786). Many younger women took advantage of the war

to leave their gender behind and cross-dressed as soldiers, the better to

pursue their own wellbeing (Deborah Sampson Cross-Dresses…, 2019). That it was better to be a man at war than a

woman at any occupation casts a stark light upon women’s fortunes during this

era.

However, in the wake of the Revolutionary War, “the mothers of the republic were tasked with instilling in their sons the qualities of virtue, piety, and patriotism necessary to the young country’s future,” for which education was essential (Ware, 2015). While, as Ware observes (2015), access to segregated education was “a long way” from equality, “it was an opening wedge.” Indeed, the mothers of suffrage, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady-Stanton, were both educated women, a condition predicated by relative affluence which afforded them the liberty to pursue their life’s work. Anthony, a teacher who never married, astutely remarked on the grim dichotomy facing her sex: “I do not want to give up my life of freedom to become a man’s housekeeper. If a girl marries poverty, she becomes a drudge. If she marries wealth, she becomes a doll, and I want none of either.” (One Woman, One Vote, 1995) Her determination to retain her economic independence was no doubt a significant factor behind her ability to remain a staunchly active figure in the Women’s Movement until her death: better able to protect her own economic health, dispossessed by neither a feckless husband nor his descendants, with the right to access and manage her own economic resources, she was not reduced to working as a drudge or to homelessness in her twilight years for lack of a man to “cover” her.

By this time, the “New Woman” had formerly-unthinkable

access to the value of her own labor, a condition which paid dividends in

self-determination and overall wellbeing for American women. By 1910 women were 20% of the workforce;

while marriage was still the dominant social goal and most wages were “turned

over to their mothers,” these working women still utilized their newfound

economic clout to engage in commercialized entertainments and leisure (Ware,

2015). With the newfound economic value

of their labor, women were also newly able to engage in protest for better

working conditions, such as the strike led by the International Ladies Garment

Workers Union staged just two years before the tragic Triangle Shirtwaist Fire

(Ware, 2015). However, these rights and

advantages were at the leading edge of labor activism; in 1920 a meager 8% of

women belonged to a union, with those women not working for a wage facing

raising living costs, poverty, extraordinary overwork due to the lack of

mechanized appliances, and disease (Ware, 2015). Desperate for agency and resources in the

face of these trials, a not-insignificant percentage of women took advantage of

farm co-ops or homesteading statutes.

The women who remained in the cities were increasingly engaged in

collective action for the betterment of labor conditions and gender equality

alike: Alice Paul, a highly-educated Quaker from a wealthy liberal-minded

family, coordinated a diverse coalition from all classes and races that

agitated tirelessly for suffrage. Paul

was convinced that social work and charity were impotent means to improve

society and help women: only the vote could give women the power to safeguard

their wellbeing and interests, and it was impossible to effectively agitate for

the vote without some measure of economic agency to facilitate the struggle.

While winning the vote was centrally important to women’s

ability to safeguard their welfare, suffrage did not nullify the central

importance of economic self-sufficiency, although it did give women superior

avenues by which to ensure it. This

framework provided the grounds upon which multiple scions of modern feminism

were able to uplift themselves in the face of severe childhood poverty, by

virtue of their ability to earn and keep wages.

In Coming of Age in Mississippi, Anne Moody chronicles the desperate

poverty of her sharecropper childhood home, which she was able to escape by

virtue of both an academic scholarship and the money she was able to earn on

her own recognizance. Without the money

she scraped together tutoring, dishwashing, waitressing and other such jobs,

Moody would have not been able to either feed herself or pay her tuition. In contrast, Judge Sonia Sotomayor was also

the recipient of financial aid, but she did not have to work her way through

high school or college despite her immigrant family’s poverty; instead, it was

her mother who worked tirelessly after the death of Sonia’s father to support them

both and further their educations (Sotomayor, 2013). This financial agency enabled them to move to

a safer neighborhood and provided the young Sonia with the investment of an

Encyclopedia Britannica, among other investments, which contributed not only to

the safety and security of their home life but also enabled Judge Sotomayor to

make the most of her considerable intellect.

Issues of economic self-sufficiency continue to affect

women, dictating the outcome of such welfare issues as child care, divorce, elder

care, and access to reproductive health services. Without financial agency, the thousands of

women who chose divorce through the ‘70s, in one of “the greatest political

acts many of us committed” (Makers Pt. II, 2013), could not have opted for

better lives. While divorce is often

proposed to be a negative consequence of feminism, this accusation neglects the

intolerable circumstances women and their children suffer without the capacity

to end a marital relationship, for which economic self-determination is vital. Furthermore, despite Roe v. Wade, sufficient

financial independence remains critical to a woman’s ability to obtain an

abortion in many states, with some populations residing 100 miles or more from

the nearest clinic; only women with sufficient resources, independence and the uncommon

privilege of being able to take time off work are able to access these rights

(Mogensen, 2018). Women’s lower wages in

comparison to men, combined with gendered child care responsibilities, leave

women disproportionately at risk for poverty, with women of color at greatest

risk (Bleiweis et al., 2020), a situation preconditioned by the lack of an adequate

child social safety net and a completely inadequate federal minimum wage. By the time COVID-19 arrived on the world

stage, American women were so disadvantaged by depressed wages, a lack of paid

leave and a disproportionate burden of childcare that the gender pay gap

widened into a “shecession,” in which women have left the workplace in

disproportionate numbers and many have been left homeless, wiping out years of

workplace gains (Rockeman et al., 2020).

As Karen Nussbaum put it in Makers… Part III (2013):

…There was a failure of the women’s movement to focus more on the economic issues of working people. It should have been about creating an alternative that worked for most women, and that alternative would have included child care… community services... [and] after-school care… I think that’s the great failure of the women’s movement.”

In conclusion, the statement “Throughout U.S history a

woman’s capacity for economic self-reliance is the most important determinant

of her well-being” is well-supported by numerous examples throughout history

and remains true today, to the extent that that labor issues are now considered

by many to be matters of women’s rights.

From the colonial era in which human trafficking and feme covert laws

made some women property and dispossessed the privileged remainder, through the

period in which women’s education and earning capacity were valued only as a

means to educate children, through the tumultuous suffrage era and the time of

the working woman in which self-sufficiency was increasingly accessible, the

extent to which any woman has been able to obtain and maintain financial

self-determination has had a critical influence on her agency and

well-being. The extent to which this

fact warrants demarcation from labor interests in general is a reflection of

women’s historical disenfranchisement and the specific ways in which United

States law has been used to disadvantage humanity’s largest minority.

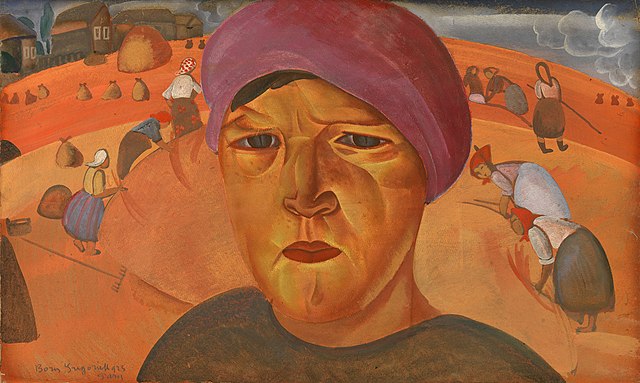

The painting is "Russian Peasant Women, 1923," by Boris Grigoriev (1886-1939)

REFERENCES

Bleiweis, R., Boesch, D., & Gaines, A. C. (2020, August

3). The Basic Facts About Women in Poverty. Center for American Progress.

Retrieved from https://americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2020/08/03/488536/basic-facts-women-poverty/

Brooks, J. F. (1996). “This Evil Extends Especially ... to

the Feminine Sex”: Negotiating Captivity in the New Mexico Borderlands.

Feminist Studies 22, 279-309.

Deborah Sampson Cross-Dresses to Fight the British (feat.

Evan Rachel Wood) - Drunk History. (2019). Comedy Central. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1tUfxNIlnqY&ab_channel=ComedyCentral

Hening, W. W. (1823). The Statutes at Large: Being a

Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, from the First Session of the

Legislature, in the Year 1619 as excerpted in “The Laws of Slavery and Freedom.”

New York: R & W & G Barlow.

How America Invented Race | The History of White People in

America. (2020). [Animation]. WORLD Channel. Retrieved from https://www.wgbh.org/programs/2020/07/06/the-history-of-white-people-in-america-episode-one-how-america-invented-race

Living Through War and Revolution: Rachel Wells, Petition to

Congress. (1786). National Archives.

Makers: Women Who Make America, Part II: Changing the World.

(2013). PBS.

Makers: Women Who Make America, Part III: Charting A New

Course. (2013). PBS.

Mogensen, J. F. (2018, May 15). This map depicts abortion

access across America and it’s really bleak. Mother Jones. Retrieved from https://motherjones.com/politics/2018/05/this-map-depicts-abortion-access-across-america-and-its-really-bleak/

Moody, A. (1992). Coming of Age in Mississippi. Dell.

One Woman, One Vote: American Experience. (1995). PBS.

Phillis Wheatley. (2021, April 9). Wikipedia. Retrieved from

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phillis_Wheatley

Phillis Wheatley clip from series “Great African American

Authors.” (2014). Centre Communications, Inc. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ex7mY8HMMnw&ab_channel=ambrosevideo

Rockeman, O., Pickert, R., & Saraiva, C. (2020,

September 30). The First Female Recession Threatens to Wipe Out Decades of

Progress for U.S. Women. Bloomberg News. News. Retrieved from https://bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-09-30/u-s-recovery-women-s-job-losses-will-hit-entire-economy

Sotomayor, S. (2013). My Beloved World. Vintage Books, a

division of Random House LLC.

Ware, S. (2015). American Women’s History: A Very Short

Introduction. Oxford University Press.

No comments:

Post a Comment