Crossing genres is hot business these days: science fiction mysteries, paranormal romance, romantic thrillers, Jane Austen with horror, steampunk love stories, you name it. A certain amount of this mixing-and-matching is marketing. Publishers are always looking for something that is both new and "just like the last bestseller." An easy way to do this is to take standard elements from successful genres and combine them.

As a reader, I've always enjoyed a little tenderness and a tantalizing hint of erotic attraction in even the most technologically-based space fiction. For me, fantasy cries out for a love story, a meeting of hearts as well as passion. As a writer, however, it behooves me to understand why romance enhances the overall story so that I can use it to its best advantage.

By romance, I mean a plot thread that involves two (or sometimes more) characters coming to understand and care deeply about one another, usually but not necessarily with some degree of sexual attraction. This is in distinction to Romance, which (a) involves a structured formula of plot elements -- attraction, misunderstanding and division, reconciliation; (b) must be the central element of the story; (c) has rules about gender, exclusivity and, depending on the market, the necessity or limitations on sexual interactions. These expectations create a specific, consistent reader experience, which is a good thing in that it is reliable. However, the themes of love and connection, of affection and loyalty, of understanding, acceptance and sacrifice, are far bigger.

In my own reading and writing, I prefer the widest definition of "love story."

After all, people

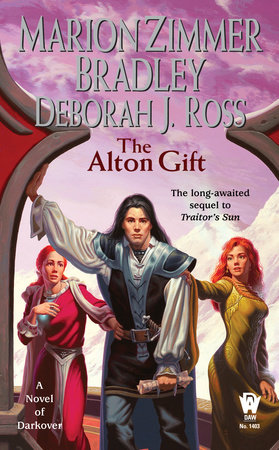

can love one another without sexual attraction and people can love more than one other person, usually in different ways and to different degrees. (For an example of what I'm talking about here, see my Darkover novels, Hastur Lord and The Alton Gift, which involve a three-way love triad in which each character must deal with the others with honesty and compassion.) With the addition of non-human characters -- aliens, angels/demons/vampires/werewolves, faeries and other magical creatures, sentient computers and the like -- the possibilities multiply enormously.

I believe that action/adventure, regardless of the genre, is deepened and enhanced by romance, and also that love stories work better when the level of peril is intensified. For one thing, both adventures and falling in love (or growing in love, or discovering that love has always been there) both involve a character taking a risk. Whether the character goes after the evil Empire, battles a dragon, lands on an unexplored planet -- or opens her own heart -- there is always the possibility that something may go terribly wrong. All too often, safe stories are boring stories. Something must be at stake, and the higher the stakes, the more reasons we have to care about what happens.

I've never subscribed to the cliche of the hero and heroine falling into one another's arms, consumed with lust, in the middle of frenzied life-or-death conflict. (My libido certainly doesn't work that way, which might be the explanation.) Such a moment might be the occasional for realizing how much one character cares for the other, when at any moment the beloved might be killed/captured/brainwashed/turned into baby-alien fodder. That moment of inner honesty escalates the stakes for the character (and, hopefully, the reader). I like to see that realization played out and savored, not exposed and consummated in wham-bam-thank-you-m'am style.

Love stories are not just about connecting with another person; they are about connecting with ourselves. In good love stories, the character struggles with internal obstacles -- memories, ideologies, character flaws -- as well as external ones. In romantic adventure, the two types of conflict mirror one another. Neither is resolvable without the other. The heroine cannot defeat the dragon until she masters herself. (Or, in a tragedy, the hero's own nature becomes his undoing; for example, Orpheus.)

Both love and crisis can force a character to re-examine her priorities. What's really important -- the way her hair looks or the thousand Bug-Eyed Monsters about to invade her home town? Who does she want to be -- the social butterfly or the executioner? Rambo or Mother Teresa? Miss Marple or Indiana Jones? Buffy or Albert Einstein?

Who does she love? What is she willing to do to protect those she loves? What will she do when faced with a choice between her own happiness and the fate of a stranger -- or a planet -- or a race of magical beings?

Romance allows us to "ratchet up the stakes" in these decisions, pitting personal concerns against altruism, what is right against what is self-serving. Adventure allows us to play out the journeys of the heart in the outer world, exploring more deeply the transformative and healing nature of love itself.

As a reader, I've always enjoyed a little tenderness and a tantalizing hint of erotic attraction in even the most technologically-based space fiction. For me, fantasy cries out for a love story, a meeting of hearts as well as passion. As a writer, however, it behooves me to understand why romance enhances the overall story so that I can use it to its best advantage.

By romance, I mean a plot thread that involves two (or sometimes more) characters coming to understand and care deeply about one another, usually but not necessarily with some degree of sexual attraction. This is in distinction to Romance, which (a) involves a structured formula of plot elements -- attraction, misunderstanding and division, reconciliation; (b) must be the central element of the story; (c) has rules about gender, exclusivity and, depending on the market, the necessity or limitations on sexual interactions. These expectations create a specific, consistent reader experience, which is a good thing in that it is reliable. However, the themes of love and connection, of affection and loyalty, of understanding, acceptance and sacrifice, are far bigger.

In my own reading and writing, I prefer the widest definition of "love story."

After all, people

can love one another without sexual attraction and people can love more than one other person, usually in different ways and to different degrees. (For an example of what I'm talking about here, see my Darkover novels, Hastur Lord and The Alton Gift, which involve a three-way love triad in which each character must deal with the others with honesty and compassion.) With the addition of non-human characters -- aliens, angels/demons/vampires/werewolves, faeries and other magical creatures, sentient computers and the like -- the possibilities multiply enormously.

I believe that action/adventure, regardless of the genre, is deepened and enhanced by romance, and also that love stories work better when the level of peril is intensified. For one thing, both adventures and falling in love (or growing in love, or discovering that love has always been there) both involve a character taking a risk. Whether the character goes after the evil Empire, battles a dragon, lands on an unexplored planet -- or opens her own heart -- there is always the possibility that something may go terribly wrong. All too often, safe stories are boring stories. Something must be at stake, and the higher the stakes, the more reasons we have to care about what happens.

I've never subscribed to the cliche of the hero and heroine falling into one another's arms, consumed with lust, in the middle of frenzied life-or-death conflict. (My libido certainly doesn't work that way, which might be the explanation.) Such a moment might be the occasional for realizing how much one character cares for the other, when at any moment the beloved might be killed/captured/brainwashed/turned into baby-alien fodder. That moment of inner honesty escalates the stakes for the character (and, hopefully, the reader). I like to see that realization played out and savored, not exposed and consummated in wham-bam-thank-you-m'am style.

Love stories are not just about connecting with another person; they are about connecting with ourselves. In good love stories, the character struggles with internal obstacles -- memories, ideologies, character flaws -- as well as external ones. In romantic adventure, the two types of conflict mirror one another. Neither is resolvable without the other. The heroine cannot defeat the dragon until she masters herself. (Or, in a tragedy, the hero's own nature becomes his undoing; for example, Orpheus.)

Both love and crisis can force a character to re-examine her priorities. What's really important -- the way her hair looks or the thousand Bug-Eyed Monsters about to invade her home town? Who does she want to be -- the social butterfly or the executioner? Rambo or Mother Teresa? Miss Marple or Indiana Jones? Buffy or Albert Einstein?

Who does she love? What is she willing to do to protect those she loves? What will she do when faced with a choice between her own happiness and the fate of a stranger -- or a planet -- or a race of magical beings?

Romance allows us to "ratchet up the stakes" in these decisions, pitting personal concerns against altruism, what is right against what is self-serving. Adventure allows us to play out the journeys of the heart in the outer world, exploring more deeply the transformative and healing nature of love itself.

No comments:

Post a Comment